Thursday, October 22, 2009

Dave McKean film

Dave McKean, who did the best of the Sandman art, is working on a film based on one of his comic books. read more here!

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

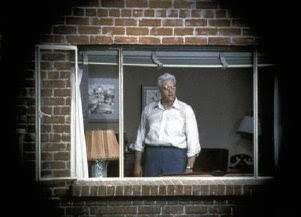

Tension and Dual Voyeurism: Hitchcock and Mulvey

"The mass of mainstream film, and the conventions within which it has consciously evolved, portray a hermetically sealed world which unwinds magically, indifferent to the presence of the audience, producing for them a sense of separation and playing on their voyeuristic fantasy." -Laura Mulvey, in her essay "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema"

What is the significance of audience voyeurism in Rear Window?

Obviously, voyeurism is a major theme of Alfred Hitchcock's Rear Window. The main character, LB Jefferies (portrayed by Jimmy Stewart), engages in a great deal of voyeuristic behavior via the titular window of his apartment. But the interesting aspect of the voyeurism in Rear Window is that it is bifurcated; the audience is very much a part of Jefferies' voyeurism as well as engaging in their own, a duality that serves to make the audience painfully aware of their own scopophilia in contrast to Laura Mulvey's quote above.

One way in which Hitchcock accomplishes this is to make the audience very aware of the camera. Hitchcock is constantly reminding the viewer of the act of filming and viewing, by having Jefferies constantly using his own cameras and optical equipment to spy on his neighbors. Not only does Rear Window give us shots of Jefferies using a camera, but we are also permitted to see exactly as Jefferies sees, through his eyes and through the lens of the camera. Hitchcock accomplishes this effect by rounding off the edges of his image, giving us a circular frame instead of a square one. This makes the audience implicit in not only their own voyeurism, watching the characters in the film play out their plot, but also in Jefferies' voyeurism, watching the lives of his neighbors.

What is the significance of allowing the audience to participate so directly in Jefferies' voyeurism?

By regularly using Jefferies as a catalyst by which he can direct the audience's voyeurism, Hitchcock causes the audience to identify with his protagonist to a great degree, and closes the gap between audience and character, erasing the "sense of seperation" mentioned by Mulvey. Although audiences regularly sympathize, empathize, or support the protagonists, they are rarely transported into that character, but Hitchcock uses Jefferies to achieve exactly that. This makes the final showdown between Jefferies and the murderous Lars Thorwald (Raymond Burr) that much more intense: here is a situation where we most certainly do not want to be in Jimmy Stewart's shoes. And although we might try at this point to distance ourselves mentally from Jefferies as his death seems imminent, Hitchcock again robs us of our voyeuristic distance by having Jefferies try futilely to use the flash on his camera as a means of keeping the killer at a distance. But just as Jefferies fails to stop Thorwald with his means of voyeurism, so too is the audience unable to distance themselves from Jefferies by their means of voyeurism. What follows is a violent, chaotic physical confrontation that capitalizes on the connection Hitchcock has worked so hard to develop.

What is the significance of the voyeuristic tension created by Hitchcock?

By clearly "playing on our voyeuristic fantasy" as Mulvey claims all mainstream film does while simultaneously depriving us of the safety of our seperation, Hitchcock is creating tension. Hitchcock enhances this tension by never letting our voyeurism pay off. All of the truly horrific elements of the film take place offscreen: Thorwald murdering his wife, the murder of the dog, etc. So we are not truly witness to any of the "action," only ancillary events and secondhand evidence. We hear a scream, and that is our only direct perception of the murder. This auditory cue is then picked up when Jefferies can hear Thorwald climbing the steps to come for him. The auditory hallmark of impending violence cues our voyeuristic desire, and here we have it, in the total darkness of Jefferies' apartment: we will finally get the release of our voyeuristic tension, when we see what has been obscured and witness what goes on the dark. This echoes what Laura Mulvey notes (via Freud) as the "desire to see and make sure of the private and forbidden."

(other topics to consider further: sexuality and physical inadequacy in Rear Window, gender roles, social structure, etc.)

What is the significance of audience voyeurism in Rear Window?

Obviously, voyeurism is a major theme of Alfred Hitchcock's Rear Window. The main character, LB Jefferies (portrayed by Jimmy Stewart), engages in a great deal of voyeuristic behavior via the titular window of his apartment. But the interesting aspect of the voyeurism in Rear Window is that it is bifurcated; the audience is very much a part of Jefferies' voyeurism as well as engaging in their own, a duality that serves to make the audience painfully aware of their own scopophilia in contrast to Laura Mulvey's quote above.

One way in which Hitchcock accomplishes this is to make the audience very aware of the camera. Hitchcock is constantly reminding the viewer of the act of filming and viewing, by having Jefferies constantly using his own cameras and optical equipment to spy on his neighbors. Not only does Rear Window give us shots of Jefferies using a camera, but we are also permitted to see exactly as Jefferies sees, through his eyes and through the lens of the camera. Hitchcock accomplishes this effect by rounding off the edges of his image, giving us a circular frame instead of a square one. This makes the audience implicit in not only their own voyeurism, watching the characters in the film play out their plot, but also in Jefferies' voyeurism, watching the lives of his neighbors.

What is the significance of allowing the audience to participate so directly in Jefferies' voyeurism?

By regularly using Jefferies as a catalyst by which he can direct the audience's voyeurism, Hitchcock causes the audience to identify with his protagonist to a great degree, and closes the gap between audience and character, erasing the "sense of seperation" mentioned by Mulvey. Although audiences regularly sympathize, empathize, or support the protagonists, they are rarely transported into that character, but Hitchcock uses Jefferies to achieve exactly that. This makes the final showdown between Jefferies and the murderous Lars Thorwald (Raymond Burr) that much more intense: here is a situation where we most certainly do not want to be in Jimmy Stewart's shoes. And although we might try at this point to distance ourselves mentally from Jefferies as his death seems imminent, Hitchcock again robs us of our voyeuristic distance by having Jefferies try futilely to use the flash on his camera as a means of keeping the killer at a distance. But just as Jefferies fails to stop Thorwald with his means of voyeurism, so too is the audience unable to distance themselves from Jefferies by their means of voyeurism. What follows is a violent, chaotic physical confrontation that capitalizes on the connection Hitchcock has worked so hard to develop.

What is the significance of the voyeuristic tension created by Hitchcock?

By clearly "playing on our voyeuristic fantasy" as Mulvey claims all mainstream film does while simultaneously depriving us of the safety of our seperation, Hitchcock is creating tension. Hitchcock enhances this tension by never letting our voyeurism pay off. All of the truly horrific elements of the film take place offscreen: Thorwald murdering his wife, the murder of the dog, etc. So we are not truly witness to any of the "action," only ancillary events and secondhand evidence. We hear a scream, and that is our only direct perception of the murder. This auditory cue is then picked up when Jefferies can hear Thorwald climbing the steps to come for him. The auditory hallmark of impending violence cues our voyeuristic desire, and here we have it, in the total darkness of Jefferies' apartment: we will finally get the release of our voyeuristic tension, when we see what has been obscured and witness what goes on the dark. This echoes what Laura Mulvey notes (via Freud) as the "desire to see and make sure of the private and forbidden."

(other topics to consider further: sexuality and physical inadequacy in Rear Window, gender roles, social structure, etc.)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)