What is the significance of Identity in John Carpenter's "The Thing"?

Obviously, identity is a concept at the forefront of the film, since the plot deals so extensively with the main characters trying to establish who is rightly themselves and who is 'The Thing', a process which quickly gets out of hand. But aside from their specific identities, the concept of identity as a whole is called into question through the film. Ultimately, the scientists are unable to solve their problem: almost all of them die except MacReady (Kurt Russell) and Childs (Keith David), and at the end neither the audience nor the characters themselves can know if either of the survivors is in fact truly themselves. What Mac and the others are really trying to solve is not simply the murder of a shapeshifting alien, it is a problem of resolving identities. Are the people we know, befriend, and work with truly the people we believe them to be? Our identities are constructed through our actions, beliefs, and language, but they are also dependent on a complex set of social symbols and interactions. As Childs says, "If I was an imitation, a perfect imitation, how would you know it was really me?"

Of course, Julia Kristeva could have told us this was the inevitable ending: "Even if human beings are involved with it, the dangers entailed by defilement are not within their power to deal with." The Thing defiles the borders of identity, occupying the physiological selves of the other scientists and representing itself as them in every possible way. The Thing exposes the "frailty of the symbolic order," and causes the scientists to question how they can ever really know who is who, or even what it means to be oneself. As the new concept of identity proposed by The Thing comes into existence, their individual identities become irrelevant: they either art The Thing, or they aren't.

MacReady's quote at the top of this post posits a particularly interesting question of identity not as a personal quality, but as a social one, comprised basically of belonging or not, a reading of identity that makes it inherently divisive, interesting in light of Kristeva's commentary regarding the warring of the masculine and feminine, of religious prohibition meant to separate men and women.

What is the significance of this problem of identity to the horror genre?

Although calling into question our sense of self is horrific enough on its face, Kristeva illuminates how "Excrement and its equivalents stand for the danger to identity that comes from without: the ego threatened by the non-ego, society threatened by its outside, life by death." In this passage, we are reminded of one crucial aspect of our identity which we rarely are even conscious of: the aspect of being alive. This is truly at the root of our identities, and comprises the basest sense of self we are afforded.

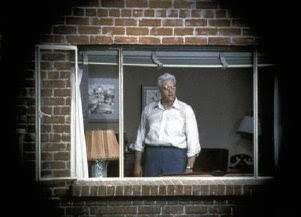

In the end of The Thing, this is dealt with in a most curious way: even though Childs and Mac are neither one certain that they have succeeded in their mission to wipe out The Thing, they are content to not kill each other. Childs asks "What do we do now?" and Mac simply responds "Why don't we just wait here for a little while... see what happens," further evidence of humanity's inability, in the final analysis, to deal with this crises of defilement of identity. In the end, Childs and Mac (or The Thing, if one of them is) decide to capitulate to the shared aspect of their identity: alive.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)